Like a River to the Sea

Junior golf success took the author to the University of Texas, where he met his bride-to-be. When she was lost aboard United 93, he began a search for meaning in her life, and death. A revelation came in the most unexpected place. Excerpted from "Like A

Excerpted from "Like a River to the Sea: Heartbreak and hope in the wake of United 93," published by Rare Bird Books.

I grew up in Muncie, Ind., the so-called Middletown, USA, where my father, Leon, took a job as controller at the Ball Corporation. When my friends and I weren’t jumping off 100-foot cliffs into the rock quarries or “bumper-hopping” on icy roads while clinging to the back of speeding cars, organized sports were a big part of my youth. I played basketball and football, but golf was where I really excelled; I won my first junior club championship when I was 9, beating kids who were two and three years older. My dad shared a love for the game, and we played many rounds together. When I was 12, we were watching the Crosby Clambake on TV. It was snowy and miserable in Muncie, and I was mesmerized by the images of Pebble Beach on the screen, with the green grass and blue ocean glittering in the sunshine. All the pros and their amateur partners were wearing stylish clothes and having a great time, and I said to Dad, “I want to be one of those guys someday. How do I get there?”

“Work hard, save, and invest your money,” he said. Those words were burned into my memory.

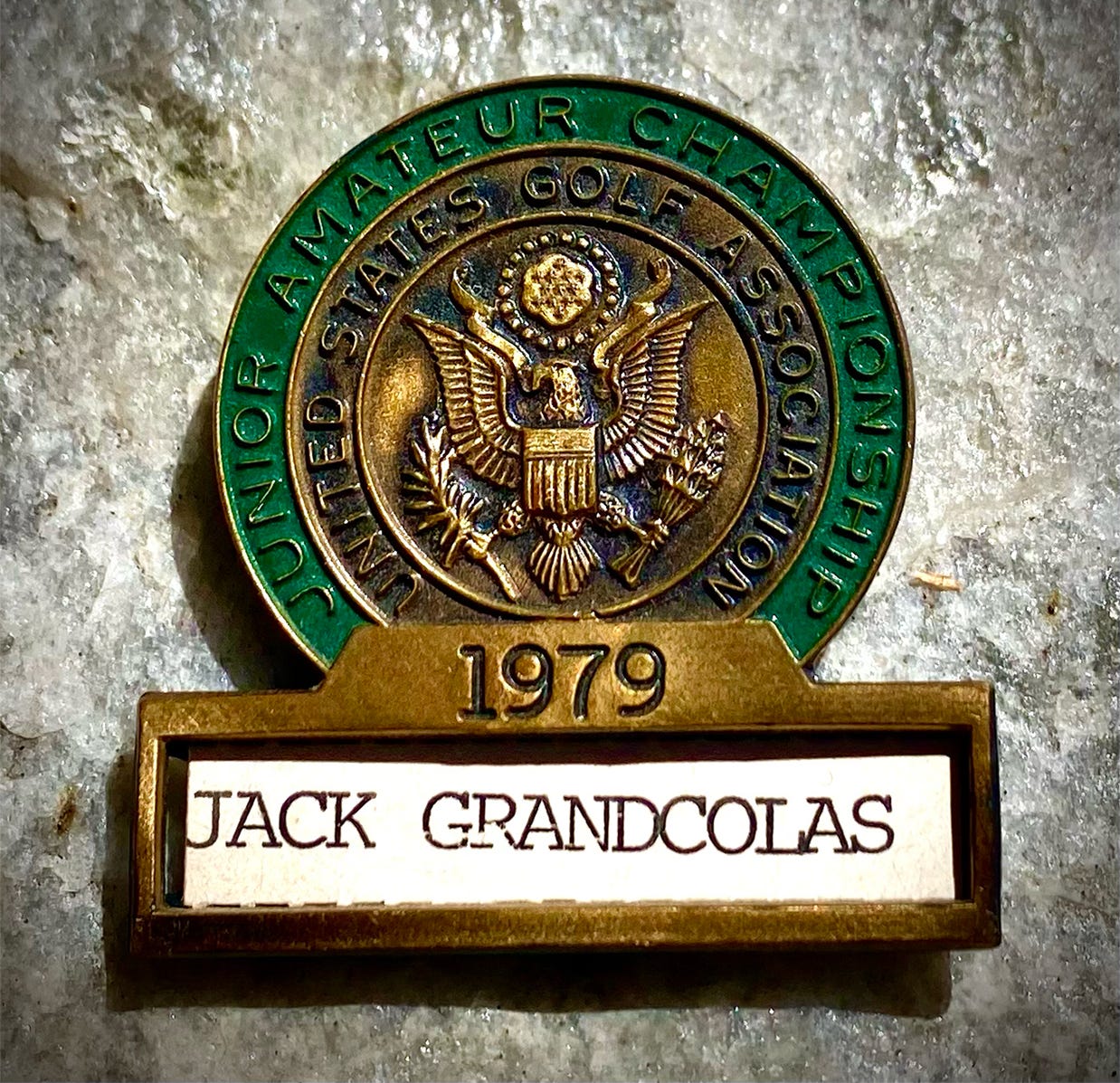

I continued to excel at golf as I reached my teenage years. In 1979, I qualified for the U.S. Junior Amateur Championship in Hilton Head, S.C. I played well against a field of the best juniors in the country, and that helped me realize that golf could be my ticket out of Indiana. When it was time to go away to college, I chose the University of Texas. My brother Mark was an alumnus and had told me plenty of stories about a great school in a fun town teeming with beautiful coeds. The warm weather in Austin was appealing too, as it would allow me to work on my game year-round. I earned a spot on the freshman golf team. Only the five best players on the squad secured a place in the tournament lineup and I was always on the fringe, which made every round stressful. I thought my dream was to join the likes of upperclassmen Mark Brooks, Brandel Chamblee and Lance Ten Broeck on the varsity squad, but after one season I realized they were at a different level skill-wise, and that I was burned out from all those years of junior golf. I left the team and embarked on a double major of communications and partying.

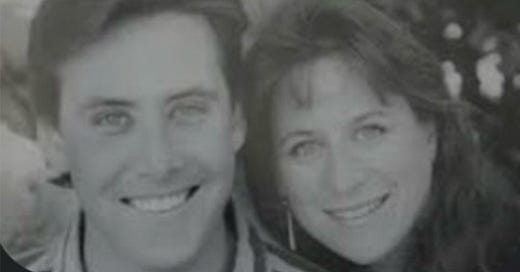

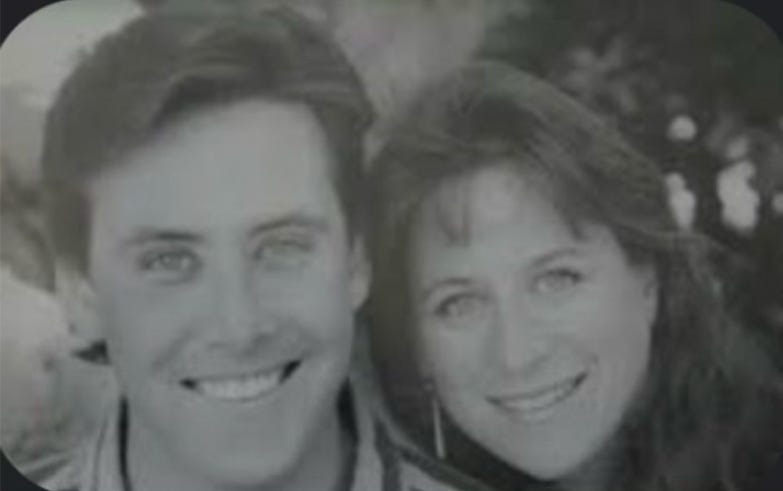

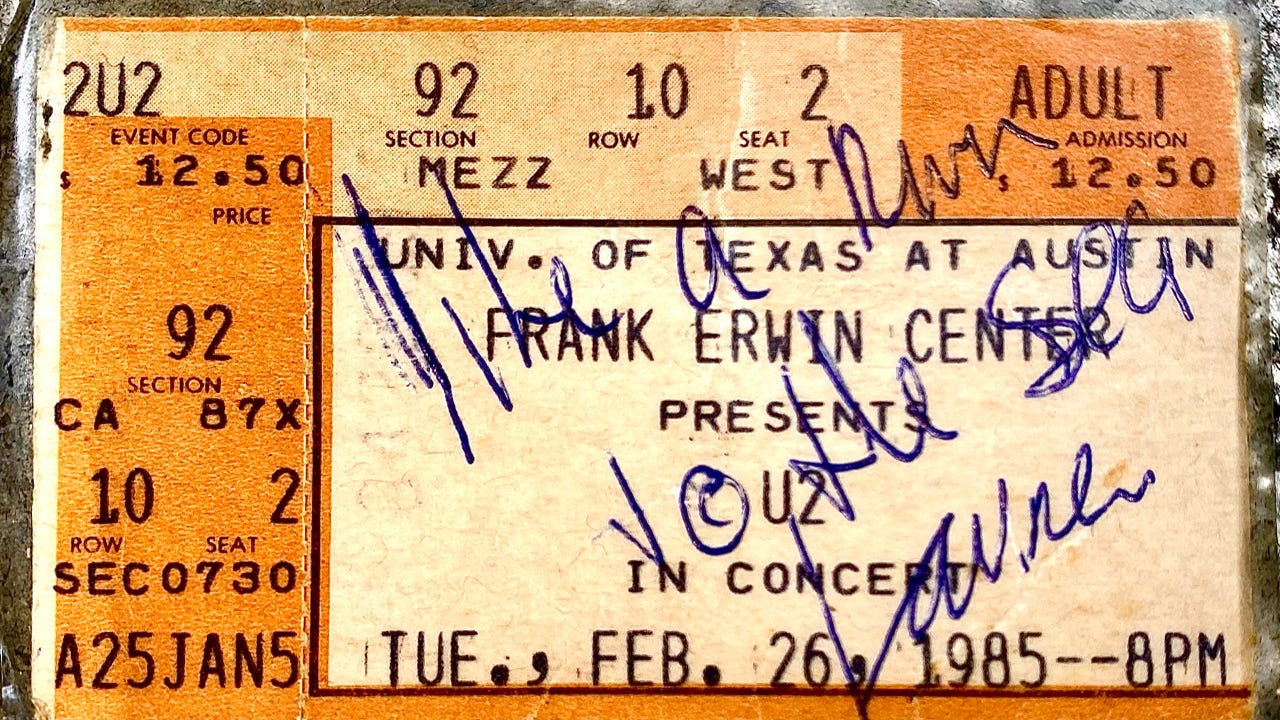

During my sophomore year, in 1983, I took a course in government studies with a friend of mine from Sigma Phi Epsilon. Walking into the classroom on the first day, we bumped into a high school friend of his from Houston: Lauren Catuzzi. He introduced us and I vividly remember thinking, Oh, my god, these are the most beautiful blue eyes I have ever seen. She had a cute smile too, and such a spirit about her. I was immediately smitten. I called Lauren one night under the guise of looking for my friend, who was dating her roommate. I knew full well he wasn’t there, but I wanted to chat with Lauren. I was too nervous to ask her out, but we had a nice conversation and I felt a rare ease with her. She mentioned that she was interested in a band I’d never heard of called U2. They were coming to town soon, so I bluffed that I had access to tickets and then worked feverishly to get them in hand. Lauren was euphoric when I told her.

On the night of the concert, I showed up at her place with a bottle of wine and a bouquet of flowers. She had left the apartment door open for me. When I tapped on the doorframe, she was brushing her teeth, so she called out, “The money’s on the counter, just leave the ticket.” I was still standing there, dumbfounded, when Lauren came out of the bathroom. Seeing me with the flowers and the wine was her first inkling that I wanted to take her on a date, not just serve as a ticket broker. She paused and then said, “Oh, it’s a date. That’s great!” After that awkward start, we had a blast at the concert. She adored Bono, and I loved listening to Lauren belt out the words to every song. We quickly fell hard for each other.

Lauren and I were married in San Francisco in the summer of 1991. She became involved in charitable fundraisers for everything from AIDS and cancer research to animal welfare. She took scuba lessons, knowing it was a passion of mine, and we had some unforgettable undersea adventures. As her 30th birthday approached, Lauren said she wanted to do something big, but she wouldn’t tell me what. It wasn’t until the morning of her birthday that she announced we were going skydiving. I think from the look on my face she could tell I was a little apprehensive, so she added, “Well, I’m going skydiving—you don’t have to try it.” Thanks to Lauren’s fearless example, I took the plunge. For the video of the jumps, Lauren chose her favorite U2 song, “One Tree Hill,” to serve as the soundtrack. She always gave it a little extra when singing the chorus: “We run like a river to the sea.”

* * *

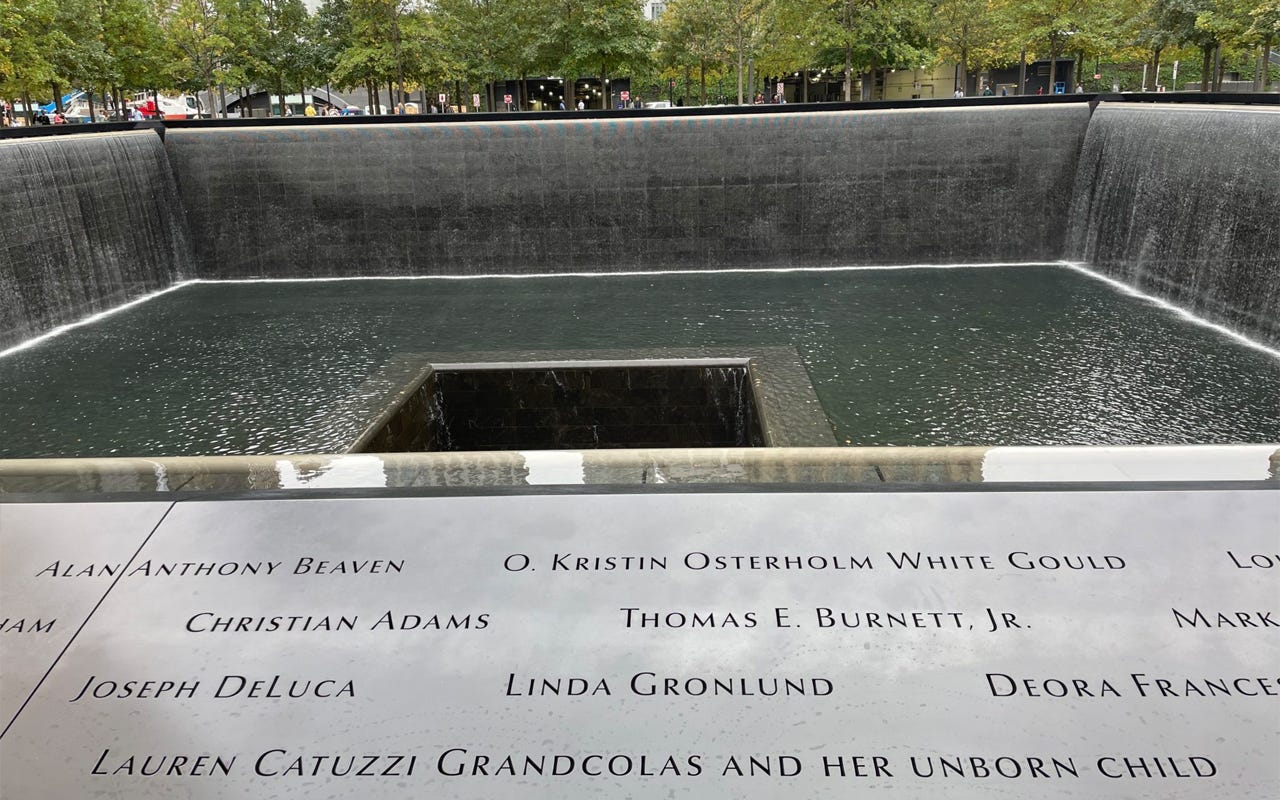

On Sept. 6, 2001, Lauren flew from our home in Northern California to New Jersey. It was a freighted trip. Her dear grandmother, Vivian Catuzzi, had died and she was going back east for the funeral. I wanted to go too, but our old cat, Nicholas, was having health problems. That orange tabby was Lauren’s spirit animal, and she insisted I stay home in San Rafael to take care of the cat. Lauren and I both traveled a fair amount for work, so we were used to saying goodbye, but this parting was one of our most emotional. I was quite fond of Little Grandma, as Vivian was known, and was sorry I couldn’t be there to support my wife. But there was also a joyous feeling because Lauren was carrying a secret: She was three months pregnant with our first child, and after Little Grandma’s funeral she was planning to share the good news to lift her family’s spirits.

We were giddy at the thought of becoming parents, having spent the previous decade trying to get pregnant. There had been plenty of heartbreak along the way, including a miscarriage in 1999, when Lauren was 36. Two years later, we had pretty much resigned ourselves to raising only cats…and then a miracle happened. On her last night in New Jersey, Lauren called and gave me an enthusiastic recounting of the big reveal of her pregnancy. I always loved talking to her on the phone. She had the cutest little voice, so full of life, and especially so on this night. I promised I would be there to pick her up at the airport the next day—September 11.

Our house had two stories, and we slept upstairs. (The nursery was to be just down the hall.) Those were the days of intrusive calls from telemarketers, so I turned off the ringer on the phone in our bedroom and fell asleep with a smile on my face. I was awakened early the next morning by the distant sound of the answering machine in the kitchen downstairs. I rolled over and snoozed a little more. When I opened my eyes again, they went right to the clock: 7:03. And then the damnedest thing happened. I looked out the bay window facing the bed and saw a spirit. Even now it seems unbelievable, but I know what I saw: the shape of an angel, opaque around the edges as if glimpsed through a drop of water, rising toward the heavens and out of view. I laid in the bed for a few moments, overwhelmed. All I could think of in that moment was, Whom do I know who recently died? Then it occurred to me that perhaps it was Little Grandma. Back then, I was not a spiritual person, but I felt humbled and grateful to have been visited by this otherworldly being.

I floated out of bed, checked on the cat, and then turned on the television news—my usual morning routine. I began shaving but was distracted by the confounding sight on the TV of smoke pouring out of both Twin Towers. The awful images kept coming: Suddenly the Pentagon was on fire, and then came reports that a plane was down in the Pennsylvania countryside.

Like every American, I was sickened by what I was watching. But I wasn’t worried about my wife. The TV commentators said that planes had been grounded nationwide, and my first instinct was that Lauren was stuck in Newark. My initial concern was for my older brother, Jim, a pilot for American Airlines who often flew out of New York and Boston. The phone rang, and I expected it to be Lauren with an update. It was her sister, Vaughn, with whom she had been staying.

“Is Lauren with you?” I asked.

“No, she left early,” Vaughn said, and a little current of panic ran through me. “I haven’t heard from her. I thought she might’ve contacted you.”

Then Vaughn said something that made the hair stand on the back of my neck: “Lauren called and told me she was able to get on an earlier flight.”

That was when I remembered the answering machine.

I bolted downstairs and saw the flashing red light indicating a new message. Lauren was one of those people who always cut it close getting to the airport but was so charming in her apologies you could never be mad at her. That morning she had been booked on a 9:20 a.m. flight from Newark to San Francisco but somehow arrived at the airport early enough to be asked if she’d like a seat on a flight that was scheduled to depart an hour and 20 minutes earlier: United 93.

The first message was Lauren calling me from Newark to inform me of the change to her itinerary, though she didn’t mention the flight number. Listening to her sweet voice, I could feel my heart pounding. I shouted out, “Please be okay. Please be okay!” On the TV were images of a smoldering hole in the ground in the Pennsylvania countryside. At that moment the commentators were saying they believed that plane had originated in Chicago, and I breathed a huge sigh of relief…but where was Lauren? The next message played. It was her calling from the plane; in those days there were credit card–activated phones hardwired to the seat backs. Lauren had worked as a marketing manager at PricewaterhouseCoopers. It was a high-pressure job, and she was often surrounded in the boardroom by alpha males in Brooks Brothers suits. But she was utterly unfazed because her father, Larry, had been a football coach and she grew up on the sidelines among all that testosterone. Lauren was a standout tennis player in high school and ever after embraced pressure moments; for a big meeting with Nick Graham, the founder of Joe Boxer, Lauren persuaded all of her dubious male colleagues to don colorful Joe Boxer underwear over their gray flannel suit pants, and Graham was so tickled by the stunt he hired PwC on the spot. So it was no surprise that on the answering machine Lauren’s voice was clear and strong, almost businesslike. “Honey, are you there? Jack? Pick up, sweetie. Okay, well, I just want to tell you I love you. We’re having a little problem on the plane. I’m fine and comfortable and I’m okay for now. I just love you more than anything, just know that. It’s just a little problem, so I, I’ll…Honey, I just love you. Please tell my family I love them too. Bye, honey.”

I fell to the ground and began sobbing. At that moment I knew that Lauren and our baby were gone. The next time I looked at the TV, the crash site in Shanksville, Pa., was being shown and the announcers were saying that early reports indicated the downed plane was United 93 out of Newark. There didn’t appear to be any survivors.

Later, I would find out that Lauren’s plane fell to the earth at 10:03 a.m. That’s 7:03 in California. The angel who visited me in the sky through the bedroom window wasn’t Little Grandma. It was Lauren.

* * *

In the months that followed I rarely left the house. In the bleakness there were always a couple rays of sunshine: Kimi Beaven and Dorothy Garcia. Each lost her husband on United 93. I had gotten to know them a little bit on the trip to Shanksville a few days after 9/11, and in the months afterward they became a big part of my life. I would talk by phone to one or both of them nearly every day. The calls could last for hours. They helped break up the isolation and loneliness. We were all grappling with shock, denial and stress, and in that state it’s easy for the mind to do strange things. I’d say, “I can’t stop thinking this—am I going crazy?” And Dorothy or Kimi would invariably say, “I was feeling exactly the same way.” That was always a relief. We would take turns cheering each other up, and that felt good too. I had always been there to provide emotional support for Lauren, and there was a warm familiarity in playing that role for Kimi and Dorothy, as they did for me.

That first holiday season was particularly tough. Lauren loved to put up a big Christmas tree and fill our home with cheer. I couldn’t muster the energy for any of that, so the house was quiet and barren. One day in mid-December, I was on the phone with Kimi, feeling particularly morose. She said that we both needed to get out of the house. I mentioned that I had an invitation to a Christmas party that night but didn’t really want to go, and certainly not alone. Kimi perked up when she heard that. “That’s it, we’re going to the party,” she said. “I’m getting in my car and driving over to your house and you can’t stop me.” And that’s exactly what she did. After so many hours on the phone, it was the first time we had seen each other since the trip to Shanksville. What a hug that was.

The party was at the house of Nick Graham, the Joe Boxer founder who had been so impressed with Lauren when he brought his business to PricewaterhouseCoopers. He lived one town over from me in Kentfield. There were maybe three dozen people there, and it was a pretty sparkly crowd. Kimi and I hid out on the patio, keeping to ourselves. We were huddled in conversation when the actor and director Sean Penn strolled up, asking if either of us had a light.

“So, how do you guys know Nick?”

I let out a big sigh, and that’s when Kimi put her hand on my chest and said, “I’ll take care of this.”

She told Sean that we had each lost our spouse on United 93. He squinted at us, took a drag of his cigarette, and said, “I’ve got a hero’s poem for ya, would you be okay if I share it?” And then he recited like a poet the lyrics to “Heroes,” a song about love and loss by the L.A. band David & David. It was a powerful bonding moment, and after that Sean integrated us into the party, making introductions and watching over us. I guess Sean could see I was hurting and a bit lost, and he felt for me. I didn’t care that he was a movie star, it was just nice to have someone with whom to talk about life. Kimi and I stayed at the party until nearly 2 a.m. Before we left, Sean and I exchanged phone numbers and he encouraged me to keep in touch. I doubted we’d even talk again, but over time we became friends.

At some point I told Sean the story about my first night out with Lauren being at a U2 concert and how she didn’t know it was a date until I showed up at her door with wine and flowers. After telling it, I pulled out my wallet and removed the ticket stub from that show, which I had carried with me every day since. I told Sean that I felt an even deeper connection to U2 because at one of their concerts in the aftermath of 9/11, they displayed on a screen the names of every person who had been killed in the attacks. A friend of mine happened to be at the concert and sent me a picture of Lauren’s name alighting the screen. Sean loved every bit of the story.

In 2005, U2 announced an upcoming concert at the Oakland Coliseum. I was delighted when Sean told me he would get tickets for me and a group of his friends; I had seen the band perform only once since that first date with Lauren two decades earlier. Sean was friendly with Bono, and unbeknownst to me, he rang him up and shared the whole story of Lauren and me. Sean asked if he would dedicate a song to us at the concert, and Bono happily agreed, until he heard it had to be Lauren’s favorite, “One Tree Hill.”

“I’ll do any other song but that one,” Bono said.

He explained to Sean that “One Tree Hill” was written for Greg Carroll, a New Zealander of Maori descent. In 1984, while the band was on tour, Bono was roaming around Auckland late at night when he had a chance encounter with Carroll. They wound up making a pilgrimage to a volcanic peak that holds spiritual significance in Maori culture. Its name is Maungakiekie, which translates to “one tree hill.” Carroll became Bono’s close friend and was hired as a soundman for the band. In 1986, on a rainy night in Dublin, Carroll died in a crash while riding Bono’s motorcycle. The lyrics for “One Tree Hill” came to Bono at Carroll’s funeral, as he reflected on their first night together. According to band lore, the song was recorded in only one take, because Bono was too overwrought to sing it twice. It had been more than 15 years since U2 performed “One Tree Hill” in concert because it remained highly emotional for the band.

It will probably come as no surprise to hear that Sean Penn can be utterly relentless. He kept pushing Bono to do “One Tree Hill” for Lauren and me, and Bono kept saying no. On the night of the concert, Sean didn’t know what was going to happen. A big group of us road-tripped to the Coliseum and were given special seats in a small staging area near the technicians operating the lights and mixing boards.

U2 put on a great show. For the final encore, the Coliseum went dark and then Bono and The Edge came out with acoustic guitars, under lonely spotlights. Bono walked to the microphone, bowed his head and said, “This song is for beautiful Lauren.” A jolt of electricity ran through my body. I looked at Sean and asked, “Did he just say what I think he said?” He just gave me a wily smile but didn’t utter a word. I knew right then something big was happening. With deep feeling in his voice, Bono began singing “One Tree Hill”: We turn away to face the cold, enduring chill/ As the day begs the night for mercy, love/ A sun so bright it leaves no shadows/ Only scars carved into stone on the face of earth/ The moon is up and over One Tree Hill/ We see the sun go down in your eyes. When he got to the chorus, he changed the prepositions in honor of Lauren. She runs like a river on to the sea/ She runs like a river to the sea. Bono was unable to go on. “God bless you, Lauren,” he said, ending the song early. It was surreal. It was beautiful and magical.

The night was far from over. We were invited to the band’s after-party on the top floor of the Four Seasons in San Francisco. Right away Sean gave a toast to the band and then brought Bono over to me. He was so warm and kind. I told him that the lyrics to his songs had taken on different meanings for me since Lauren’s death. I quoted a riff from the song “Walk On”: You’re packing a suitcase for a place none of us has been/A place that has to be believed to be seen. Bono took off his blue-tinted sunglasses and looked deep into my eyes. “Oh, you get that now, do you?” he asked. “Don’t worry, you’ll get to see Lauren again.”

I wanted so badly to believe him, but I couldn’t feel it in my heart. I told Bono, “You’re a very religious man and you have belief. I was brought up Catholic, but I don’t practice anymore. I’ve had some experiences that renew my faith, but I still struggle. Being brought up Catholic, you’re given all this guilt about things that you didn’t do right. I worry that I may have screwed up in this life and mortgaged my opportunity to see Lauren again.”

Bono put his hand on my shoulder and said, “You’ll see her again. You’ll see her again. I know it. We all screw up in life.”

“But I’ve screwed up plenty of times.”

“We all screw up, Jack. I screwed up just four days ago. That’s why God grants us forgiveness. It’s his most powerful gift.”

Those words hit me hard. At that moment I felt unburdened. Ever since 9/11, I had questioned God and his plan for me. What Bono said finally gave me new hope, and a profound belief that I would get to see Lauren again on the other side. The night was a tribute to her, but in a very important way it set me free, allowing me to be more forgiving of myself and rekindle my belief in God’s mercy. Bono brought up the underlying meaning of “One Tree Hill,” saying, “The river is the journey we are all on, the sea is the afterlife. It’s where we all meet again. I think there’s a reason why your Lauren loved that song so much.”

At that point, Sean interrupted the conversation to ask, “Did you show him the ticket stub?”

I had been too embarrassed to say anything, but Bono wanted to see it. I fished the stub out of my wallet, and he studied it carefully, including the date: Feb. 26, 1985.

“Lauren loved you at that concert,” I said to Bono. “She spent the whole night virtually ignoring me and staring at you. She only married me because she couldn’t have you.”

He giggled and then asked, “May I sign it?” Bono sat down in a chair. In careful script, he wrote, Like a river to the sea, Lauren. Then he turned it over. See you for a swim, Bono.